Memorial Day

A reminder that progress

Has come at a price

I recently had the extremely good fortune of taking a trip to Paris, France with my family. Walking centuries-old cobblestone streets into ancient structures that people have used and revered for hundreds of years feels like swimming in the deep ocean, where you can’t see the bottom.

In the 4th century AD, Paris was a walled fortress on an island in the River Seine, on what is now the Île De La Cité. When you step foot on this small landmass, you follow in the steps of Vikings who lay siege to Paris in the 9th century. The expanse of history alive all around you is mesmerizing.

I was mostly excited to visit Paris because of the shared history between the United States and France. Having owned vast tracks of what is now the USA, and fighting wars both against and on behalf of American colonists, France has arguably had as big an influence on the United States as any country on earth not named Great Britain.

In “The Greater Journey,” historian David McCollough chronicles pilgrimages made to Paris in the 19th century by aspiring American writers, artists, and doctors. They wanted to partake in the highest levels of education and training in the humanities, arts, and medicine available in the world at the time. There was one place on earth where an American could find these things: Paris.

The reading material I brought along for our trip is a great historical non-fiction book called “Blood And Treasure: Daniel Boone and the Fight For America’s First Frontier.” I was expecting the book to educate me about a key figure in the mythology of colonial America, and tell stories about the origins of the region where I live and have so much family history. Kentucky was, after all, the paradise of Daniel Boone’s dreams and where he ultimately made his home (at Fort Boonesborough along the Kentucky River).

The book is a vivid chronicle of the expansion of American colonists over the Appalachian Mountains. Boone is a main character, but he is far from the only character. Prior to the French and Indian War, the frontier West of the Appalachians was owned either by indigenous tribes or the French.

The French And Indian War was one in a chain of conflicts between America’s native peoples and its rapidly expanding population of colonists. The general cadence went: colonists wanted to expand into new lands, Britain brokered a deal with the French and/or one or more tribes to allow some limited form of colonial settlement, the colonists either violated the deal or manipulated it to their advantage, violence escalated, war broke out.

These conflicts saw the introduction of biological warfare in the form of smallpox-infected blankets. They saw prominent British military leaders like General Jeffrey Amherst openly advocate for the extermination of Indians from the face of the earth. Both settlers and the tribal war parties murdered each other’s men, women, and children so frequently that, when reading a chronicle of the period, it gets difficult to distinguish one atrocity-filled event from the next.

If Thomas Jefferson’s view was correct, that blood shed from patriots and tyrants is a “natural manure” for the tree of liberty, the 18th century American frontier was a fertilizer festival.

There are 1,113 panels of Stained Glass in Saint Chapelle. It seems like far too small a number when you’re in their presence. It is overwhelming, like all of the instruments of a vast orchestra playing every note of a symphony at the exact same time.

Looking at my daughters’ awe-struck faces, none of it made sense. How could this place, echoing with the revenant prayers and awe-inspired whispers of multitudes over centuries, be congruous with a nation whose soldiers scalped children younger than my girls in the normal course of war?

For as many panes of stained glass as there are in all of the cathedrals of Europe, there are many multiples of that number of humans who have died violent deaths at the hands of other humans, all to advance some kind of progress. The fact that we ever emerged from that wilderness – to the extent we’ve emerged from it – is a miracle.

As horrible as it can be to read about human history, it creates a lens wide enough to view some of the context of whatever troubles we’re enduring now. Those troubles exist as data points on a curve that has been trending in many positive directions for many decades, or longer.

For example:

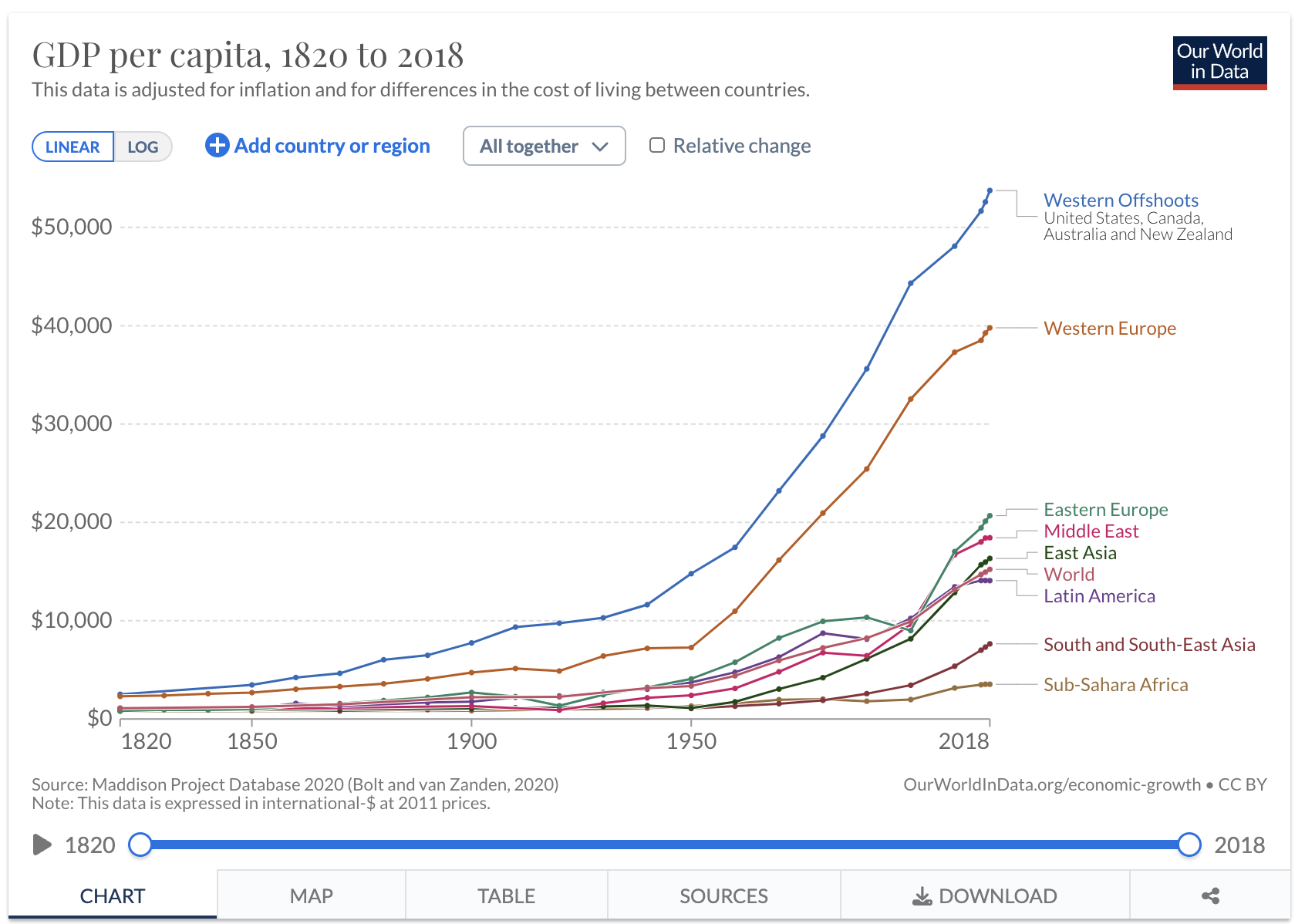

Per capita Gross Domestic Product has been growing around the world for over 200 years:

Women around the world are increasingly educated to the same extent as men:

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/gender-ratios-for-mean-years-of-schooling

A host of diseases like smallpox, malaria, polio, guinea worm, measles, mumps, and rhubella, and are all either eradicated or on the path to eradication.

The percent of the human population with access to clean drinking water and sanitation has been steadily climbing for the past 23 years:

And, since World War II, there has been a volatile but consistent trend downwards in the number of deaths in state-based conflicts (fancy speak for “war.”):

Memorial Day, of all the days in the long year, is the day we’ve chosen to remember the people who have refreshed the soil of “the tree of liberty” with their lives. For most of the rest of the year, priorities tend towards ever greater aspirations of something better. More money in the bank, better income, a better job, a better vacation, a better car, a new tv, gentler facial exfoliants, smarter smartphones, etc.

But Memorial Day is the day to remember what we have and how we’ve gotten it. It has never been easy. “Retirement,” for example, only became a problem when people began regularly living deep into old age, which can be seen as the fruit of fewer wars and better medicine. History teaches that it has taken a lot of manure to grow that fruit.

From all of us at SeaCure, we wish you a restful and contemplative Memorial Day.

(877)328-4037

(877)328-4037